A MONTH OF MAGICAL THINKING: ENTERING ROOMS

- nekbone69

- Dec 5, 2024

- 13 min read

(For a matter of months I’ve drafted an entry intended for this blog and every approach to the keyboard was met with a cleansing sigh of defeat. Maybe I’ve lost it, I thought.

But in those same months, I’ve also wondered about spending the month of November writing. its funny to consider: After NaNoWriMo nearly cancelled itself only now do I feel up to the challenge of it. Hacking through an attempt at breaking a story. But doing it for myself. Not thousands of words per day, but as much I could. Not as a public stunt or attempt at social media virality. Just for the exercise. Just to test how far I might get.

What follows is a (raw, barely edited) sample of writing I attempt last month. I don’t know what it’s about. How dare you ask. Its about people entering rooms.

Truth: The cast features twin characters I invented (or who visited me) years ago. The location is slightly based on a house party I went to that I’ve never quite forgotten. I wanted the twins to enter the house and get downstairs to the basement where there’s a famous DJ, but one who doesn’t like being around a lot of people. A couple of weeks ago, I had a vision I wondered if it would work. Here’s the boys entering the house to visit DJ TEN-TILL, whose given name is Curtis:)

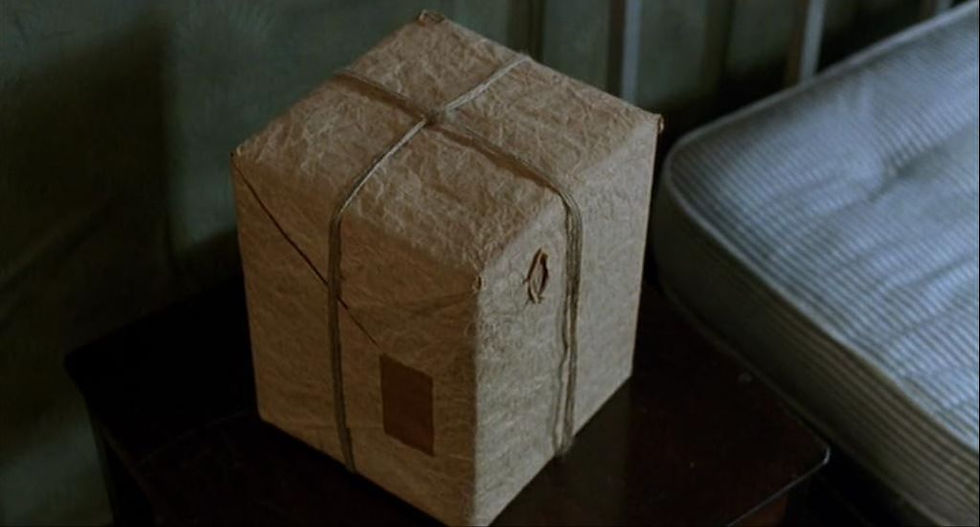

The living room was dark and bounced from the storm surge of shadows as people danced at the front door then across the entire living room space. Black waves rising and falling, breathing simultaneously. As Rail and Ram pushed through, they noticed the crowd was mostly older and seniors. Gray uncles and slightly heavy set aunts sweating beneath oversize glasses. Steel speckled goatees, well manicured snowy Afros. The room smelled medicinal with alcohol and vintage colognes. One man, most free in an oversized pair of painter’s pants, waved his arms and shuffled back and forth under possession of the music. The boys pushed through the throng, guided through the darkness by rope lights anchored in every corner. Speakers were suspended from the corners of the ceiling and pummeled the room with fistfuls of bass. The boys crossed through the dancers into the dining room which was now a line of mostly unoccupied folding chairs next to a dining table that had been shoved to the far side of the room. A few people sat holding red cups on their knees watching the shadows dance. As they moved through, Ram noticed in the far corner of the room behind the displaced and the heavily draped window, there was a hospital bed, glowing in the darkness from a bank of sheets and blankets. A woman lay awake in the darkness, her eyes sparkling light, her long gray hair was spread across the pillow like moss. Ram couldn’t identify details of the woman’s face, but saw one thin arm reach up for something floating just out of reach before her, her arm a brittle branch bracketed with an oversized white tag. Her lips and hollow jaw chewed words muted by the music filling every corner. They followed the pathway of a long plastic carpet runner into the fully lit kitchen. The counter space resembled a landfill with opened packages and evidence of everything having been rummaged. Two liter soda bottles, half and quarter filled bottles of scotch and gin, empty tubs of chicken containers and clear plastic jewel boxes of potstickers and fried rolls, flaking biscuits and three open bags of different kinds of potato chips seemed to lick at the air in translucent flames. Bottles of half used hot sauce and ketchup, mustard. Stacks of white picnic plates and forks in ripped plastic. Tupperware containers and a stove populated with pots of opaque broth and grease. Near the backdoor, a tall garbage can overflowed with stained plates and wax paper and dirty Styrofoam bowls. Across the hallway from the kitchen, the bathroom door swung up and they both looked and saw Lettie clumsily emerge and click off the light. She appeared drowsy from drinking but her voice rose upon recognizing the boys. “Twins!” She called and flung her arms open to them both. At once the three sloppily hugged one another, all crowded in the doorway. She slipped between them and cheered for herself, suddenly dancing the Bump, her hips bouncing off one boy to the other. “Y’all make yourselves at home.” She grunted and bumped. “Get you something to drink. Get you something to eat. Get whatever y’all need.” The boys demurred on drinking and instead asked after her son, Ten. “Curtis ain’t going nowhere,” She said. “You can hear him.” She gestured to the throbbing air. “Go make sure he alright. And ask where that Al Green at? Tell him to play more Funkadelic. I still got liquor left to drink.” Opening the basement door releases a phantom of sweaty air, like having an overstuffed blanket shaken in your face. The boys climbed down the stairwell into the room which was humid and akin to stepping into a bath. The room was a hoarded collage of milk crates, storage containers and boxes of all sizes stacked to every corner of the room. A library of sloppy vinyl records, dvd’s, DAT tapes, instrument cases. Centered amongst the clutter was a bed where Curtis lay naked beneath a sheet that wrapped around him in a sloppy toga. He was triangulated by equipment in what appeared to be a music control center. A beat legend in the neighborhood, known as DJ TEN-TILL, Curtis made money from dee-jay’ing, curating mix-tapes and producing original beats for local underground and nationally known rap artists. Curtis weighed somewhere between 650-700 lbs. and was the same size as the mattress he lay on. A huge spider in a web of electronic devices, he appeared a spillage of skin, his arms and chest dissolving into the sheets and fabric of the bed. His head was square as a speaker and crowned with fraying finger-thick braids pointing like antennae. Wires from his headphones fell across his mountainous chest mimicking a black iv cord. The bed was framed with several steel articulating arms which supported turntables and mixing units. From his left or right, he could swing over a mixer, turntable or laptop then swing it back out of the way without having to otherwise move. A matrix of pulleys made the entire room available to him at the mere pull of a color coded bungee cord. His music fed directly upstairs into the speakers stationed around the house. In the basement, the sound was muted except for the thumps from the dancers and the bass giving the house its own heartbeat. Curtis looked up and smiled brightly as the boys entered, moving his headphones up above his ears. “Whassup, brothers.” Curtis said, adding quickly: “I don’t take requests.” “Lettie say you better play more Funkadelic.” Rail said. “Lettie need to chill with all that.” Curtis smirked and whined like an annoyed child. “Man, thas all she listen to. I’ll do Wars of Armageddon so I don’t have to hear her mouth all weekend.” Curtis fidgeted with his controllers, then pulled a headphone over one ear to dial up what he wanted, his eyes stuck on the laptop. “I ain’t expect to see y’all. Especially tonight. Old school for the old heads as I call it. What you need?” ******************************************

The next sample is a different character entering a different space. I’ve spent so much time visiting hospitals and rest homes, they have infected my imagination and stubbornly keep re-appearing. For me, the ultimate act of intimacy and love is visiting someone in hospital. I wrote this November, but in my mind it feels like a diary entry or that I’ve written this before. I haven’t. Just lived it. I remember ‘Rose of Sharon’ from the book ‘Grapes of Wrath’, unable to invent anything better in the moment:

The Rose of Sharon Home sat at the crest of the Hilltop Drive that opened like a portal into the sky. Commodore parked his truck in the first handicapped space next to the rainbow banded Rose of Sharon Commuter van. Two uniformed drivers stood cheerfully talking and tossed toothy greetings to Commodore as he waved off their attention like a repeating fly. At the entryway the bouquet of cleansers and age and wounds and illness nearly rocked Commodore back on his heels. The security at reception looked up past the older woman who was standing over her talking some impassioned grievance. The guard called out and waved: Mr Cooper, Mr Cooper, please stop for a minute. But if Commodore made any sound louder than a grunt, neither woman heard it. He marched up the hallway to the fourth door on the left and as he entered, gasped. A nurse stood alone in the room making a bed in the pool of sunlight cascading through the window, her hands flat against the sheet as if laying out a hand of cards. She was surprised to see him filling the doorway, but her expression quickly softened. “Recreation room,” She said. “Down the hall on the right.” Commodore stood self consciously picking at the fabric along the lip of his pockets before dropping his gaze and turning back into the hall. The Rec Room held a discomforting assembly of men and women bleached by time into slow moving marionettes. An arc of fifteen wheelchairs and another ten stackable chairs were spread before a piano where a middle aged man in a white shirt and tie played Chopin. A few heads turned when Commodore entered, but just as quickly returned to the music. He saw her in a wheelchair on the far side of the room staring out the window. The wheelchair sat in a perfect square of sunlight. She sat up tall, a blanket folded with mechanical neatness across her lap. Her black gray hair swept back into a quick bun. He gripped a chair a few steps away, then swung it next to her and sat down. He rubbed his knees then leaned far back in his seat. His fidgeting caught her attention and she turned, their eyes meeting briefly before something like a nod occurred but her gaze drifted back to the still life displayed, the diamond quilt of the city sparkling beneath a cloudless sky. Commodore sat and crossed his heels. Several breaths passed before he closed his eyes and stumbled softly into a brief, dreamless sleep. He was gone for a dozen or more breaths before choking awake and scratching his nose and sitting up. She was still there and far away, concentrated on the business outside the window, birds zipping through the air. He looked at her, her profile stubbornly marked and quiet, then reached over to collect, one by one, the soft fingers of her hand and held it.

How about a dialogue sample?

The aforementioned ‘Commodore’ (the name of my grandfather’s brother, a name I’ve long wanted to use) leaves the rest home for a barber shop across town, owned by an old friend of his named Coach. Unbeknownst to him, Coach recently died. The shop is newly owned by Coach’s grandson, Marzo, who invites the elder into the back office of the barber shop to talk. The barely mentioned, silent woman described earlier is Commodore’s wife, recently rendered speechless due to dementia. But Commodore, completely thrown by his wife and the news of the loss of his friend, can’t trust such a young man with his old feelings, despite the younger’s kindness.)

Marzo led the older man into the back office, lit from a huge bay window which overlooked an unexpected patio with a white table affixed with a shade umbrella. The patio was a driveway sealed off from the street and too tiny to do anything except sit. There was nappy hedges against the wooden fence and ceramic pots of aloe and elephant ears. Marzo approached a coffee maker tabled with a stack of styrofoam cups and creamer and sugar packs in a dispenser near a steel cabinet and a mini fridge. “Some coffee, Mr. Cooper?” “Won’t refuse it.” He opened a package of coffee grounds, loaded it into the coffee maker and filled the pot with filtered water from the dispenser. Commodore was looking over a corkboard where there was posted a program for the funeral of Coach Martin Barrengo, Beloved Husband, Father and Grandfather. The program was dated before Christmas the previous year. “Too much has been going on,” Commodore whispered to himself pitifully. Marzo said the word: “Heart attack.” Then watched as the man took down the program and paged through it as if it were a sacred document. “Keep that one if you want,” Marzo added. Commodore held the program and suddenly folded it and slid it into his pocket. Marzo poured two cups of coffee and passed Commodore one. He then opened a tiny fridge and took out a box of Half & Half and shook it. Commodore dug his fist through a display of sugar packets, tore open several with one smooth motion and poured them into the liquid. “It was pretty sudden. The whole family was caught off guard.” “When did you take over this place?” “Less a month before he passed, actually,” Marzo said. “He started to mentor me after I got my license and saw I was serious. First thing after high school. Got my driver’s license and my barber license within the same month. Over the last year, he started saying he’d trust the shop to me if I wanted it.” Marzo stepped behind the desk and pulled open a drawer. He reached inside and pulled out a box of Futuro cigars then flipped open the lid. “Do you smoke, Mr Cooper?” he asked. Commodore shrugged and followed Marzo out to the tiny patio. “What I call my smoker’s lounge,” Marzo said. The wooden fence made the patio intimate as a porch. Marzo placed his cup of coffee on the round table next to where an ashtray was already placed. Commodore noisily pulled back a chair and Marzo sat across from him. “I was gonna say…” Marzo said. “It seems like I heard something about Mrs. Cooper.” For the first time since entering the store, Commodore looked up at Marzo’s face. The glance felt a mild challenge but Marzo waited kindly. For Commodore, the boy strongly resembled Coach around the eyes and nose. “She done retired.” Commodore shrugged. “Its mostly me now.” Marzo cut Commodore’s cigar first and passed it to him. Then took out a lighter and started his cigar, the smoke blossoming across his face like a mask. “You open today?” Marzo asked. “There was some things I needed to do,” Commodore said. For the moment, the store felt like a debt that needed to be paid, and didn’t want to be reminded of. “Before heading back, figure I’d stop by here. Say hello. But there’s no more hello’s to be had.” Marzo nodded. “My cousin found him,” he said. “I don’t know if you remember Little Greg?” “What you mean found him?” “At home. In the garage. Stretched out on the floor like he was taking a nap. It was bad. Greg’s only 14.” “My god.” Commodore said. He ignited the lighter and touched it to the cigar. “I know, right? I couldn’t imagine. Being the one to find him like that, or being Grandad and having that happen while you were alone. That’s what kills me. And nobody can say for how long he was out there like that. It was really hard on all of us. We had service about a week later. We didn’t get to alert everybody. “ Marzo took the lighter back from Commodore and pocketed it. All while watching his face, which resembled a rock formation– ancient but sturdy. Commodore kept his gaze down to the ground as if watching something projected only for himself, a play of light and image that saddened him. His mind was fully engulfed with ghosts and memory. He seemed to review what he saw earlier at Rose of Sharon, Zolinda and all the others appearing to wait for something to find them. He wasn’t far removed from Coach nor any of the residence at Rose of Sharon and for the first time thought he, by rights, should be there with them, or at least riding the floor of a garage somewhere. That he wasn’t seemed a kind of failure on his part. What is a wife who doesn’t remember being married? What am I? Marzo watched the man think and waited for Commodore to say something, but he only sipped from his cigar. Then, like releasing a butterfly into the air, Marzo said: “I’m sorry.” “Ain’t nothing to be sorry for,” Commodore shook his head, finally. “Nothing’s promised any of us, except darkness.” “Guess I’m saying I’m sorry you didn’t get to say goodbye,” Marzo said. “Feels like I remember you as much as I do him.” “Was it a big service,” Commodore said. “Not really. His sister came up from Louisiana. Some old clients, but it was pretty small. We kept notice on the door for a while. Wasn’t no way for us to reach out to everybody, you know.” “I been tied up,” Commodore offered finally, his mind still on Rose of Sharon House.“Why it’s news to me.” “There’s been a lot going on,” Marzo said.”When Coach died, nothing stopped. Bills. The world kept on and ain’t waited on nobody to get over their hurt. I’m just sorry you found out this way. How long ya’ll been friends?” “More years than I even want to add up. It was a different world, and that’s that.” “I could hardly imagine,” Marzo said. “His shop was what inspired Zoe to open our thrift store. Had his first shop down there a bunch of years before the military bought out that area and he moved here. Must be fifteen, sixteen years ago, now.” “Sounds about right.” “Don’t nothing stay as it is. This the first time I stepped through the door and everything was different.” “I didn’t want to change it up too much,” Marzo offered. “But he insisted I make it as personal as possible. He said it was going to be my second home, and he was right. Only difference, he couldn’t use this office. The owner tried to sell it as a separate unit, a little studio or something, but was too cheap to make it its own place. So he built this out and sealed off the driveway to make it a patio and as a favor to my granddad didn’t kick up the lease too much. I had a bunch of family come down and help paint and re-decorate a little bit.” Marzo said. “You got enough help down at your place? You know I got folks come through the shop every day looking for work.” “I’m gonna need some body soon enough.” Commodore grunted. “Its been a long, long time since I had reason to think about the future.” Marzo laughed. “You’re supposed to be encouraging me about the future. Guess you ain’t considering retiring.” “I don’t even know what that is. To Retire. Pastel drawers on a golf course.” “There ain’t a thing wrong with pastel shorts on a golf course. I would take that right now, shoot. But I guess that ain’t your thing.” “I always worked. Had to. Never thought much about the end of work,” Commodore said. “I never saw myself retiring or dying.” Marzo smiled. “You loved your life.” Commodore shrugged: “If that’s what that mean.” “It does.” Marzo smiled. “It does to me.”

Comments